Title: Ishmael on the Tightrope: Satisficing Between Luddites and Transhumanists in the Age of Systemic Deification

In an age increasingly shaped by algorithms, automation, and the arcane whispers of artificial general intelligence, Ishmael walks a tightrope. He is neither saint nor engineer, neither luddite nor transhumanist. He is the watchful everyman—an archetype of human consciousness attempting balance in a civilizational systems engineering project that has long outgrown its architects. Below him, two gravitational poles pull at humanity’s soul: one anchored in the soil of the past, the other launched toward synthetic eternity.

On the left, the Luddites. Not merely machine-breakers but value-defenders. They fear the erosion of the human scale—the local, the personal, the spiritual. They see in the cathedral of technology not a sanctuary but a tower of Babel, inching us toward a divine judgment not of fire, but of forgetting: forgetting of limits, of embodiment, of nature. For the Luddites, systems engineering is not neutral; it is colonization of the organic by the abstract.

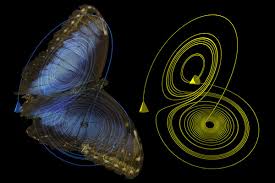

On the right, the Transhumanists. Their creed is acceleration. They dream of carbon transcended, of neural lace and sentient code. Death is an engineering failure; morality, a constraint soon obsolete. They seek not only to improve systems but to escape them—to out-evolve evolution itself. For them, God’s butterfly effect is not a caution but a design principle: one tweak of the genome, one nudge in cognition, and the entire species flutters into a new ontology.

Ishmael walks the line. He hears both sides, understands their songs. He cannot live in the past, but he also does not wish to become post-human. His aim is not to perfect civilization but to satisfice—to make choices that are good enough to preserve dignity, adaptability, and the sacred unpredictability of life. He treats systems engineering not as control but as stewardship. The planet is not a spreadsheet, nor is consciousness a software update. For Ishmael, satisficing is moral wisdom in the face of complexity—a way to honor constraints without collapsing into fatalism.

Civilizational systems engineering, at its core, is the design of feedback loops, incentives, and infrastructure that shape how billions of agents interact. But it is also metaphysical: every input echoes a vision of the human, every outcome a theological hypothesis. We cannot touch society’s code without rewriting our assumptions about meaning. Here, Ishmael senses a greater truth: even the most rational system is haunted by what cannot be measured—the butterfly flapping in God’s causality.

The “butterfly effect,” coined by chaos theory, posits that tiny perturbations can create massive, unforeseeable consequences. But when filtered through theology, it becomes something more profound: a reminder that causality is sacred, that intention resonates across dimensions we cannot chart. God’s butterfly is not just an agent of chaos; it is a sign that no system, no matter how optimized, can contain the totality of creation.

Thus, Ishmael does not reject engineering—he refines it with humility. He builds bridges between technologies and traditions, between systems theory and story. He refuses both nihilism and naïveté. His satisficing is not a compromise but a commitment: to ensure that the machinery of civilization remains in service of life, not the other way around.

In the end, the tightrope is not suspended over a chasm but over possibility. On either side, the extremes scream. But in the middle, Ishmael walks—and with each step, he draws a blueprint for a future that remains human, humble, and holy.